So the earliest forms of barbecue were probably cooked by enslaved Native Americans and white indentured servants before the transition to African slavery. “What surprised me in researching this book is that Native Americans were the first barbecue cooks, really, and that they were enslaved as well. Talk a little more about that transition. And then later when enslaved Africans increased in number, they became barbecue’s principle cooks, and added their own culinary signature to what would become barbecue.” There was also the raised platform, which is what people saw in the Caribbean, and then also a very shallow pit, where a lot of times the meat was just laid right on the burning coals.Īnd so what I argue is that Europeans saw some of this and then added their own grilling techniques. And then you bury it and come back some time later and eat that. It was like a vertical hole with a fuel source in the bottom and then layers of meat and vegetation. There was also something called an earth oven. There was spit cooking, which Europeans would have been familiar with.

In some senses, they were having sticks that were aimed towards the fire, and there would be morsels of meat kind of angled toward the fire for cooking. And there were multiple ways that Native Americans were cooking. So I argue that really, it was a fusion of Native American smoking techniques. The way that Southern barbecue emerges is just so different. Because that story is that Europeans show up in the Caribbean, they see indigenous people cooking in a way they're not familiar with, and then Europeans bring that to the North American mainland. Can you explain how barbecue’s history starts with the indigenous peoples of the Americas, and the primary cooking techniques that were used?Īdrian Miller: “The reason I start with the indigenous people in the Americas, mainly mainland North America, is that the Caribbean origin story never quite jelled for me when it came to Southern barbecue.

KCRW: The word “barbecue” has its roots in West Africa. He joins Good Food to discuss barbecue’s origins, community, and legacy.

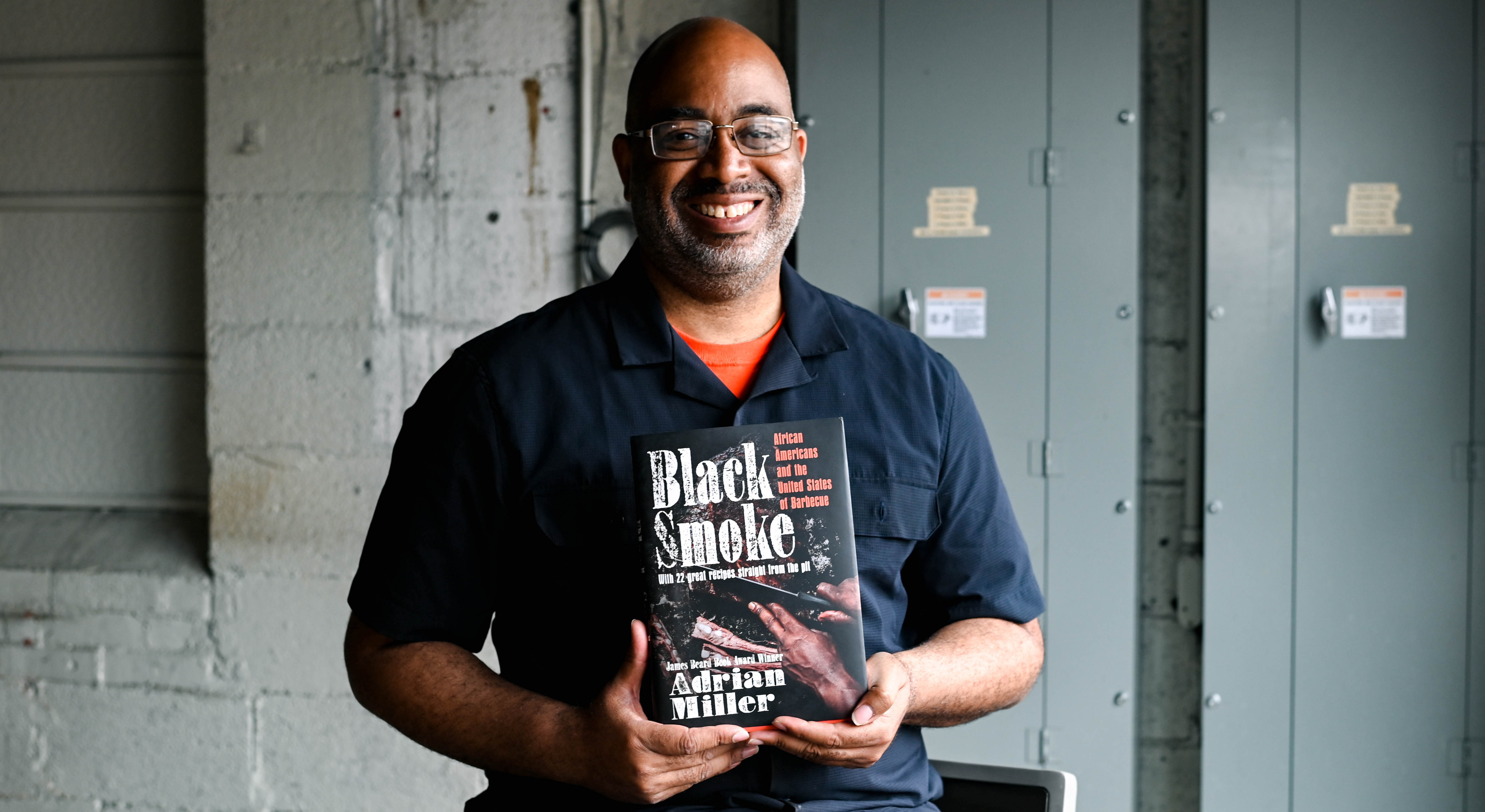

“Barbecue was one of the places where people kind of ignored the color line in terms of restaurants, and you would often find whites going into the Black neighborhood to get barbecue,” Miller says.įrom the surprising and often overlooked beginnings of American barbecue, Miller chronicles the evolution and the entrepreneurship of Black barbecue as he stokes the coals of its living legacy. In his latest book, “ Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue,” food scholar and James Beard winner Adrian Miller writes, “Black-run barbecue joints often find themselves located at the intersection of food, race, and absurdity.”

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)